Wherefore art though Direct Payments?

The title may be confusing at first glance, so let me clarify. In Shakespeare's famous play Romeo and Juliet, when Juliet says, "Wherefore art thou Romeo?" she isn't asking where Romeo is, as is commonly believed, but rather why he is called Romeo (since the central conflict is the feud between their two families, which brings the lovers great distress).

In a similar vein, I'm not asking where direct payments are, but rather questioning why they are called "direct payments" and what their purpose truly is.

Recent experiences in my work have exposed several practices that seem to contradict the very principles behind direct payments.

One key issue is local authorities requesting financial records more frequently than necessary—sometimes every three months, or even monthly in some cases. I believe this is often driven by financial teams that may lack a proper understanding of the laws and statutory guidance that should be followed (as illustrated in the case of R v Islington, where the judge clearly outlines the meaning of statutory guidance).

One reason given is that authorities have the right to know how the funds are being spent for budgeting purposes. While this may be true, is such frequent reporting proportionate? How does checking every month truly help? The budget is allocated through a care plan. Regardless of how much money is spent, it has already been assigned. Would you ask any commissioned services to submit monthly reports on their expenditure? Doesn't this merely increase paperwork, with someone having to sift through it all and input the data into a system? Is this genuinely efficient, or is it just cost-cutting at the expense of efficiency?

Even in times of austerity, the law does not allow for this level of interference. People have a right to a private family life, as protected under the Human Rights Act.

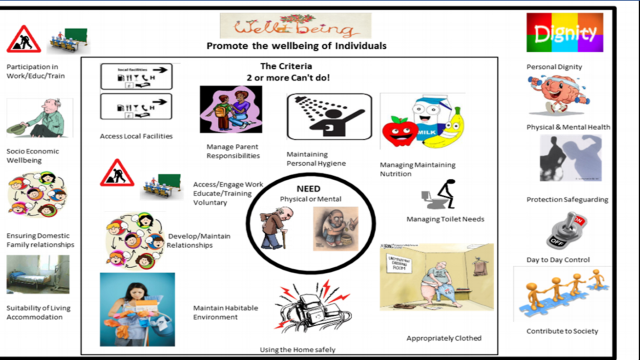

The purpose of direct payments has always been to promote independence, choice, and control for the individuals managing them. This has been made clear, with specific guidance stating that reporting requirements should not be excessive. See below for further clarification.

Documentary burdens

Administering direct payments

12.24. The local authority must be satisfied that the direct payment is being used to meet eligible care and support needs, and should therefore have systems in place to monitor direct payment usage.

The Care and Support (Direct Payments) Regulations 2014 set out that the local authority must review the making of direct payments initially within six months, and thereafter every 12 months, but must not design systems that place a disproportionate reporting burden upon the individual. The reporting system should not clash with the policy intention of direct payments to encourage greater autonomy, flexibility and innovation. For example, people should not be requested to duplicate information or have onerous requirements placed upon them.

Another concerning issue in social care is the increasing number of local authorities making significant efforts to cut costs on essential services—services that are crucial for some people and could even save lives.

Several authorities have either already removed or are attempting to phase out community alarm systems (such as Telecare or similar services).

First, it's important to remind authorities that statutory guidance specifically mentions such alarms as claimable under disability-related expenditure. This means that people receiving social care can simply claim the cost back, which only creates an additional burden for both parties involved. Annex C of the same statutory guidance lists community alarms as the first item on the list of potential expenses that can be claimed.

The most troubling aspect of this is that community alarms are vital pieces of equipment that can literally save lives. These systems allow individuals to press a button and immediately contact someone who can dispatch help or call others to assist. Without them, vulnerable people are left at greater risk, particularly those prone to falls, who could end up lying unattended for hours, leading to serious, potentially life-threatening consequences.

What is even more alarming is that Section 149 impact assessments often cite the need to save money without properly considering the broader effects or exploring other ways to cut costs. In fact, the savings from removing these systems are so minimal in the context of the overall care budget that it amounts to nothing more than penny-pinching. There are many other ways to achieve cost savings—many of which are highlighted in the statutory guidance—if only local authorities would take the time to review them.

Would authorities rather cut direct payments, despite the NHS Personalised Care Policy clearly showing that direct payments are 17% cheaper than other delivery systems? I would argue that the potential savings are even greater—up to 50% could be saved if users were given better support, enabling them to hire their own carers. This would not only address the ongoing recruitment problems but also reduce the substantial profits going to agencies, which typically charge at least 50% more for supported staff. Any claims of increased costs by agencies can easily be disproved through industry cost comparisons. Furthermore, economies of scale (the larger the operation, the cheaper it is to run) should result in lower costs for these agencies anyway.

It is crucial to consider the true purpose and costs involved when making decisions about direct payments. Some of the recent decisions made by local authorities could, I fear, become matters of life and death.

Comments

Post a Comment