Personlised Process

What is a process?

A process can be defined as a step-by-step guide that facilitates the development or transformation of a product or service to achieve a specific outcome (author’s definition). But is this definition complete, or does it require further refinement?

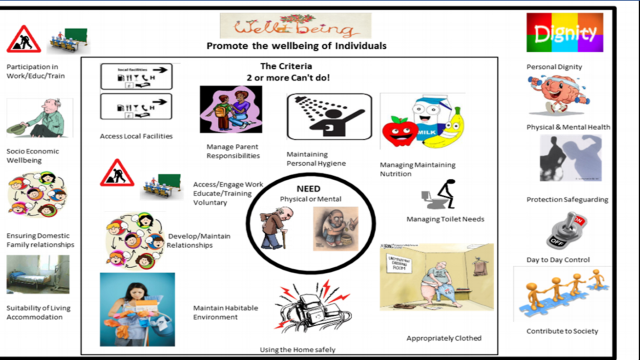

Like many others, I frequently encounter processes in the Health and Social Care sectors. Unfortunately, this is an area that often frustrates me, as I believe these processes can sometimes prevent people from achieving the outcomes they truly need and deserve.

One area that stands out in particular is the process surrounding Personal Budgets, especially when it comes to Direct Payments. This is an area where I often focus my advocacy work. Another complex issue is commissioning. The situation becomes even more challenging when these two processes intersect.

In my work, I review about five different processes each week across Health and Social Care in various regions. These processes usually start with promising intentions—independence, choice, and control are often highlighted right on the first page. However, what follows tends to stray far from these ideals, and I see this repeatedly.

So, what do I notice when I dig deeper? Time and again, it seems to boil down to a lack of trust from the organisations and service providers. While the initial intention is to promote choice and control for individuals, the layers of checks and oversight often go to extremes. In some cases, I believe these checks infringe on fundamental human rights, particularly the right to privacy.

For example, when I requested that an authority inform individuals about the checks involved in using pre-payment cards, I was told that these checks could be done at any time, without the individual being notified. My concern was met with a dismissive response: "We can't do everything." But shouldn’t following the law be a baseline expectation?

The amount of paperwork and scrutiny involved in these processes has become overwhelming—reviews have turned into full-blown assessments. This not only adds to the cost and time burden on authorities but yields very little benefit. I’m often told, "But it's the public's money," and yes, it is—money meant for the public. In fact, statutory guidance under the Care Act clearly states that paperwork and checks should be minimised and simplified. This was reinforced by an Ombudsman decision in a case where an individual with capacity issues complained that the process was too cumbersome. The Ombudsman upheld the complaint, emphasising that paperwork should be simplified and checks kept to a minimum.

It makes me wonder: Has the rhetoric, often perpetuated by certain political parties, that people on benefits are "scroungers" who don’t contribute to society, become so ingrained that service providers and statutory organisations are more focused on policing people than upholding the high principles of personalisation? Are they so caught up in this mindset that they’re neglecting their legal responsibilities?

Another key issue here is the element of risk. Even in high finance, when accounts are prepared, there's always an estimated risk factored in, and anything within that acceptable risk range is considered manageable. After all, we're human—we make mistakes. I'm not suggesting that checks shouldn't be done, but they must be proportionate and focused on real problem areas, not applied wholesale. This notion that every penny must be tracked is excessive and counterproductive.

I’m not denying that some people may misuse Direct Payments if they're not properly informed. However, when you compare the level of misuse against the total budget, it's clear the risk is minimal and likely doesn’t justify the cost of such intensive checks. It’s like dealing with shoplifting—yes, theft happens, but do we post police officers at every store entrance to check every customer as they leave? Of course not.

For personalisation to truly succeed, we need to uphold its principles not just at the start of the process but throughout the entire journey. Authorities must keep in mind that this is about people—about their choices, their independence, and their control. These values shouldn’t just be buzzwords; they need to be at the heart of every decision made.

If you're a process developer, here's a question to consider: What if it were me? What if I were denied my basic rights to live freely and have a fulfilling life? What if I was told I couldn't do certain things or go places to meet my friends?

A common response from organisations lately is that they need to be "equitable." But where is this mandate written? Care, by its very nature, cannot be equitable—it's based on individual needs, and since everyone's needs are different, so are the resources required to meet them. You can't treat every condition with paracetamol. In the pursuit of equity, you may actually be violating the Equality Act. Contrary to popular belief, the Act isn't about treating everyone the same, but about ensuring that people aren't treated less favorably by recognising their unique circumstances.

From a process perspective, this means that individuals with greater needs or fewer opportunities should be given the support necessary to bring them to the same level as others. It's about fairness, not uniformity.

I'm not suggesting that everything must be provided or that every request is feasible. I'm simply asking you to pause and consider how these restrictions might feel. Going back to the core idea of personalisation, ask yourself: Is this process truly enabling someone to move from one state to another in order to achieve a desired outcome? If the answer is no, then perhaps it's time to rethink the approach.

Comments

Post a Comment