It has to be in the Care plan?

Many Social Care and NHS Continuing Healthcare Direct Payment users are frequently told—and come to believe—that they must have every expenditure outlined in their Care Plan before they can use their direct payments.

However, those of us who have been using Direct Payments for many years know that things have changed. The independence, choice and control once promised by this scheme has, over time, been reduced to mere words.

This is a recent development, likely arising from austerity measures, but it is important to note that no new laws or policies have been democratically passed to support this shift. Personally, I believe it's simply an excuse to cut public services. While cost-saving is understandable, there are numerous other ways to save money that don't negatively impact the end user. It often feels like the drive to uphold the spirit of Social Care has dwindled, with financial officers taking more control than necessary over decisions that affect care.

I strongly contend that this was never the intended purpose of direct payments. It is neither practical nor, potentially, legal, and it limits individuals' ability to lead fulfilling lives and meet their well-being needs.

The legislation is clear: individuals are entitled to a personal budget, which determines how much money they receive. If they opt for direct payments, they are free to spend that money as they see fit, as long as it meets their assessed needs. In fact, a few years ago, I attended a council meeting where the assistant director of social care made it clear to councillors that there are very few restrictions on how direct payments can be spent—prohibited items include alcohol, tobacco, and debt repayments.

A closer look at Section 25 of the Care Act, which covers care and support plans, and the associated regulations, shows that it is not required for all spending to be itemised in the care plan. The purpose of the care plan is to ensure that needs are identified and how these needs will be met. It does not stipulate that every item of expenditure must be listed. This notion appears to be a more recent imposition, likely introduced as a means to restrict spending in today’s challenging financial climate.

The statutory guidance in fact state:Annex C (41) The care plan may be a good starting point for considering what is necessary for disability-related expenditure. However, flexibility is needed. What is disability-related expenditure should not be limited to what is necessary for care and support.” i appreciate that generally DRE's don't exist in health budgets, however the principles remain the same, speicficaly as the National framework for continuing health care is clear that health care means Health AND Care.

This was reiterated in a recent judicial review in:

RW v Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead[2023] EWHC 1449 (Admin) https://caselaw.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ewhc/admin/2023/1449#download-options

Judge Dexter Dias KC is quoted in his judgement as stating, at paragraph 53, that "What is clear is that the expenditure must be reasonable and not extravagant or disproportionate to the need it addresses. This must be viewed, it seems to me, rationally but also humanely. It is not a requirement to relentlessly search for the cheapest possible way to meet the need and restrict oneself to that, no matter what. Context is important, and flexibility is key. This is about supporting people living with disability; a sense of proportion must be applied."

This principle runs through the Guidance on assessing personal budgets, which emphasises that while value for money is important—given this is public, taxpayer-funded money—the local authority must not lose sight of the fact that outcomes should not be determined purely by financial considerations. This is explicitly stated in §11.27 of the Guidance:

“Decisions should therefore be based on outcomes and value for money, rather than being purely financially motivated.”

I highly recommend reading this case in full, as the judge makes crucial distinctions regarding disability-related expenditure. He highlights the need for authorities to consider proportionality in decision-making, especially in relation to the percentage of costs compared to the overall budget.

Disability-Related Expenditure (DRE), by its very nature, often involves unpredictable, urgent needs arising at short notice. This unpredictability is precisely why DRE exists. Expecting individuals to seek permission every time they need to spend on such costs is impractical and generates unnecessary paperwork and delays for most people.

Life cannot be planned a year in advance, and with the ongoing reduction in services, people often have to wait months for even the simplest claims to be processed. Moreover, it is essential that individuals with fluctuating needs have access to a budget that can also fluctuate to meet those changing requirements.

At the heart of this issue is trust, and the ethos of meeting people's needs alongside addressing their additional costs.

I would argue, for the sake of reasonableness and efficiency, that individuals should be permitted to spend their budgets on necessary items, particularly disability-related expenditure. To allow flexibility while balancing the local authority's need to manage financial risk, it should be clearly stated in policy that a certain percentage of the budget can be used flexibly. Receipts and justifications for expenditure should be provided, and the spending must be disability-related and support a person's Care Act needs or wellbeing principles (even if not explicitly stated).

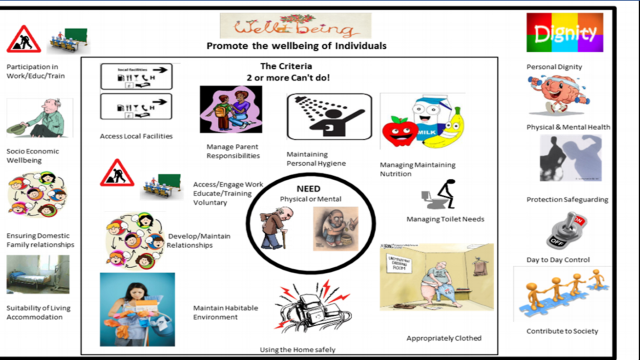

Regarding wellbeing principles, which are often overlooked by authorities despite being highlighted in statutory guidance, most people tend to focus only on physical or mental wellbeing. However, many fail to recognise that socio-economic factors are also a key aspect of wellbeing. For instance, using Scope's guide on the extra costs faced by disabled people, it's clear that the financial impact is significant—amounting to around £1050 extra per month. Despite additional benefits, this leaves people facing a considerable shortfall.

Much is often said about fraud and misuse of funds. We’ve all heard of cases where this has occurred. However, I believe that if the figures were examined, the incidence of fraud would be minimal and statistically insignificant. It’s similar to benefit fraud, which is frequently sensationalised, yet the amount defrauded represents only a small fraction of the overall budget. Moreover, the resources spent on preventing such fraud often exceed the actual amount being lost, making it a disproportionate response.

I am not suggesting that people should be free to spend their budgets however they like. They must take responsibility for managing public funds and use their budgets within the scope of their needs. However, Disability-Related Expenditure must still allow for the flexibility necessary for individuals to live their lives with dignity and autonomy.

Not sure the extra costs faced by disabled people, amount to "around £10,050 extra per month".

ReplyDeleteTypo I think?

It references Scope, which appears to report a figure £1050/month. https://www.scope.org.uk/campaigns/disability-price-tag